As 1943 drew to a close, the Italian campaign showed signs of stagnating. Watching the progress from afar, Allied leaders frowned at the slow progress of their armies who slogged north over the rivers and mountains, harried by the Germans who made them bleed for every piece of high ground.

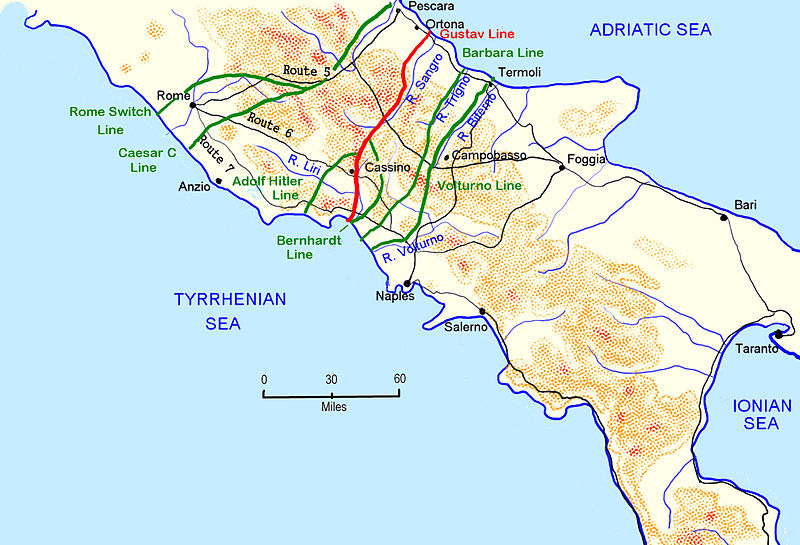

While these delaying actions were going on, the German army prepared the line they intended to hold through the winter. This Winterstellung, also called the Gustav Line, took Italy’s natural barriers and fortified them into a formidable obstacle. It crossed the breadth of the peninsula and passed a height whose name would become synonymous with the struggles of the Italian campaign: Monte Cassino.

The Situation

Monte Cassino, looming over the Rapido river and the town of Cassino in the valley below, was home to the Monastery of St. Benedict. The Second World War was not the first armed conflict to pass the monastery, which had the misfortune of being on one of the major ancient roads to Rome—the Via Casilina, also known as Highway 6.

Up this highway the Allies advanced, pushing forward until finally, after navigating the Mignano Gap, they came within sight of the Rapido Valley. The Germans had flooded the land below, making it a marshy mess, and emptied the city to blast fortifications into the rocky landscape. The monastery itself was not occupied, though Monte Cassino and the peaks surrounding it offered excellent vantage points for German observers. In this carefully prepared position, they awaited the next Allied move.

What was the next move going to be? From the start, the Allied goals in Italy were somewhat vague. They’d wanted to knock Italy out of the war. Done. They’d wanted a foothold in mainland Europe, and to capture airfields. Also done.

Somewhere along the line, however, focus had shifted to Rome. To conquer Italy, one must conquer Rome. And Rome lay past the Gustav Line. Therefore, this line must be crossed.

Or, perhaps it could be circumvented.

OPERATION SHINGLE, particularly championed by Winston Churchill, was a plan to send troops north to execute an amphibious landing on the Italian coast behind the Gustav Line in the area of Anzio. The Allied leadership hoped that by threatening German supply lines in the rear they would draw off soldiers from the Gustav Line, allowing the main force to break through and join the Anzio force. Together they would head on to Rome.

As amphibious landings are no easy feat, scheduling the timing of the attacks was essential. The strike on the Gustav Line should be timed to draw the German eyes away from Anzio—meaning that the attacks had to take place just prior to the landings.

Here’s where we see “the devil in the details.” The Anzio landings would require amphibious landing craft. The Allies only had so many of these. And they were slated to head back to Britain in preparation for OVERLORD (the Normandy landings of “D-Day.”)

With some creative scrounging, leadership provided ninety-five craft. This would allow the Anzio operation to land two divisions, some commandos and Rangers. However, getting the initial force onto the beachhead would not be enough—they’d also need supplies and reinforcements. All of this would have to happen before the landing craft were needed back in Britain at the end of February.

If it was going to happen, the Anzio assault had to take place January 22nd. This meant the 5th Army, who had finally battled through to the gateway of the Rapido Valley at Mount Trocchio on January 15th, would be going almost straight back into the fight.

The First Battle

The point to be stressed about the first battle of Cassino is that it was not a prepared offensive against the Gustav Line, but a hurried resumption of a weary advance that had battered its way to a standstill. Exhausted by weeks of heavy fighting, severe casualties, and appalling weather conditions, troops badly in need of a respite were, in effect, merely ordered to keep going.”

Majdalany pg 57

The first assault on the Gustav Line had three major parts. First, starting on January 17th over toward the coast, the British Tenth Corps would force their way across the Garigliano River and swing left, toward Cassino. The Free French Expeditionary Corps would come through the mountains to the right of Cassino. The American Second Corps would then force their way across the Rapido River just south of Cassino and get into the Liri Valley where Highway 6 continued northward so that, when the American and British force landed on Anzio, both Allied forces could link up.

Perhaps it looked manageable on paper, especially with optimistic intelligence reports coming in about low German morale.

The British and French both made some progress, though they weren’t able to push forward far. The two American regiments of the 36th Division started their attack—the main push around Cassino—on the 20th.

The Rapido River was around nine feet deep at the crossing, with the banks only 60 feet apart. This meant that they’d need to cross by boat, at night, and hope that the German forces on the other side would neither see nor hear them.

With the difficulties of hauling the boats a mile or more across marshy land, through fields of mines that had been missed by sweepers or planted since the last check, the attempt went badly from the start. The white tape that was to lead the troops through safe passages in the dark had been broken by shelling, so some groups had trouble even finding their starting lines. Others reached the river but struggled with the boats—heavy wood and canvas affairs or rubber rafts. As the banks were so close, the German forces harried them with fire, but Allied guns couldn’t provide help without putting their own men in danger.

One regiment, the 143rd, managed a crossing and had two footbridges up before dawn. However, they were quickly surrounded when daylight came and were forced to withdraw. They tried again, but were driven back a second time with terrible losses.

The other, the 141st, managed to get two companies across one footbridge their engineers cobbled together, but they were cut off with no communication. The rest of the 141st joined them under the cover of a smoke screen the next day, but they could not hold out under the tremendous pressure of the entrenched German forces. As January 22nd wore on, the first attempt to cross the Rapido River ended.

Then the American volume of fire gradually died down. From this diminuendo of sound, it became clear that they were running out of ammunition, although there were no wireless sets still working through which they could report this. By four that afternoon, it was all over.”

Majdalany pg. 65

The 36th Division had lost 1,681 men in two days. 875 were missing.

At the same time, the Anzio landings had been initially successful, though they had not drawn off fighting men from the Gustav Line. Anzio will get its own post later.

To wrap up the first battle of Monte Cassino, however, we must return to the Rapido River where General Mark Clark ordered the other U.S. infantry division that he had on hand, the 34th, to attempt to take Cassino from the north.

It was another crossing over marshy ground—which meant no tank support—followed by an icy river crossing, then a jaunt into defended mountainsides. The infantry pushed through with terrible losses, while the engineers scrambled to find a way to get them tank support. Finally, they managed to construct tank lanes using strips of wire matting that the air force used for temporary landing strips. With tank support in place, the infantry held on, then moved forward into the mountains.

It was small, but it was a bridgehead over the Rapido.

The French and the remaining regiment of the 36th came alongside to help the push. In the punishing mountainous landscape, Allied soldiers who couldn’t even dig in to the rocky soil faced German solders with armor shielded machine gun emplacements, portable armored pill boxes, and fortifications drilled into the mountain rocks.

In spite of orders to attack, to take Cassino and the Liri Valley, the remaining Allied soldiers were simply unable to do so. Wearily clinging to the cold mountainsides, by the time the survivors of the 34th were relieved by the 4th Indian Division, fifty of them had to be carried out of the mountains on stretchers because they couldn’t walk out on their own power.

At the close of the first battle for Cassino, except for the mountain bridgehead across the Rapido, the German defenses stood victorious.

However, seeing how challenging this advance would be, General Alexander ordered the Eighth Army over from the Adriatic side of Italy to reinforce the Fifth Army. The Allies prepared for the second battle for Monte Cassino, in which the 4th Indian Division and the Second New Zealand Corps would take on the mountain stronghold.

I had intended to work through the entire series of battles for Monte Cassino in one post—but even as a short sum-up, it’s just too involved. This seems like the place to stop for today, and I’ll pick up on the other battles next time. Thank you so much for stopping by!

(Updated: Here is the link to the second half of the story of Monte Cassino in WWII.)

While there are many excellent resources on the situation in WWII Italy in general and at Monte Cassino in particular—and I’ve linked to some of them throughout the article—I particularly used Fred Majdalany’s excellent account, Cassino: Portrait of a Battle to refresh my memory as a reference for this post. All quotes are taken from this book. (Official Citation Information: Majdalany, Fred. Cassino, Portrait of a Battle. London: Cassell and Co, 1957. Print.)

If you’re interested in more short summaries of the Italian Campaign in WWII, here are links to the other posts in this series:

It Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time: The Italian Campaign in WWII Part 1

Getting a Foothold: The Italian Campaign in WWII Part 2

Through the Rivers and Over the Mountains: The Italian Campaign in WWII Part 3