Welcome to another installment of my little history of World War 2!

As these accounts move into the early 40’s, keeping a straightforward, easy-to-follow time line becomes difficult. Europe was overrun, the Atlantic under constant U-boat assault, Britain besieged, Hitler’s forces engaged on the enormous Eastern Front, Rommel still vying for North Africa, and the U.S. and Japanese had just begun their struggles in the Pacific.

SO, today we’ll just focus on the Pacific, following British forces as they were pushed back towards their “impregnable” fortress at Singapore, and U.S. and Filipino forces as they struggled to hold the island of Luzon.

While in the U.S. we tend to remember December 7, 1941 as the day the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, that attack was part of a much larger plan.

Attacks on Guam, Wake and Midway Island, and on the British and Indian divisions on the Malay peninsula, left the Allied forces reeling. And these were only the beginning.

Del Shay, of the U.S. 192nd Tank Battalion Medical Staff, was stationed near Clark Field on the Philippine Island of Luzon. He recalls his first realizations that his country was at war in Frontlines World War II: Personal Accounts of Wisconsin Veterans by John Maino.

“It was at reveille, 6:00 a.m. on Monday morning, when we got the news about Pearl Harbor. Later on that morning, at about 10:30 a.m. they told us that Baguio, the summer capital in Northern Luzon had been bombed; now we were nervous. All morning our P-40’s were flying around up above us. We had B-17 bombers out on patrol, but at noon they all came back in for lunch.”

“I had just gotten back to my tent and was lying down for a little siesta when I looked up and saw this beautiful formation of planes- just perfect formation. I thought, ‘What a wonderful sight!’ About 30 seconds later the first bombs hit; I never even considered they might be Japanese planes.” (Maino 51-51)

Why General Douglas MacArthur, in charge of the U.S. defense of the Philippines, allowed the planes to be caught on the ground is, I suppose, a moot point. The unprepared United States forces lost 86 of their aircraft at Clark Field, compared to only 7 Japanese Zeroes.

Shay further describes the chaos.

“Nobody knew where to go. Guys were running across the field…running all over the place…but where could you go? We didn’t have any bomb shelters or foxholes or anything like that.” (Maino 52)

Things weren’t going much better for the British and Indian Divisions on the Malay Peninsula.

The Japanese onslaught found them out-mastered in the air. Their naval support, already stretched thin, was stretched even thinner with the sinking of the Repulse and the Prince of Wales.

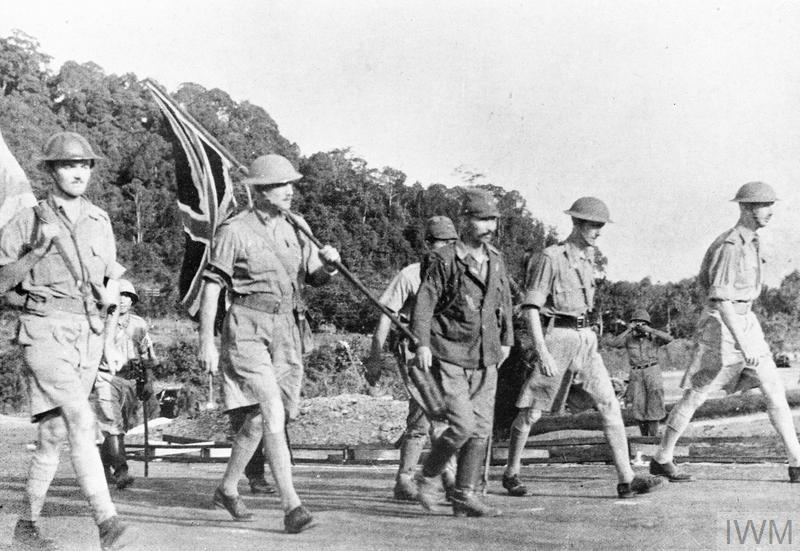

In spite of their best efforts, the Allied troops were pushed back, slowly, defensive line by defensive line.

Still, behind them was hope. The island fortress of Singapore offered safety, or at least a place to make a stand…or so the Allied leadership thought.

Unfortunately, Singapore wasn’t nearly ready for what was coming.

Back in the Philippines, Japanese forces landed on Luzon.

Perhaps seeing where things were headed, General MacArthur moved his headquarters to the fortified island of Corregidor. The U.S. and Filipino forces retired toward the Bataan peninsula from the north and south. Men from the Air force, Navy, and Marines were reorganized to serve as infantry.

By January 5th, the underprepared defenders’ rations were halved.

In the words of Shey:

“Orders came down to pack up again, this time south into Bataan. We started marching with everything we had, which wasn’t a lot. The most pitiful sight you’ve ever seen was these Filipino women and old people sitting in the ditches crying, just wailing. It was a real sad sight. They must have known what was coming. We didn’t.” (Maino 52-53)

Back in Singapore, General Wavell, (who we last met in North Africa) visited personally in mid-January. The reports he sent home to Churchill were not encouraging.

Singapore was receiving reinforcements, but they lacked training. The Indian Divisions and Australian units were inflicting losses on the enemy and holding them up, but could not stop their advance.

Worst of all, Wavell doubted that Singapore could hold out long under siege.

Singapore had been meant to be an impregnable fortress. The island certainly did have good defenses, unfortunately, they were all planned for an attack from the sea.

The landward side, the side the Japanese were advancing on, was virtually undefended.

“It was with feelings of painful surprise that I read this message… So there were no permanent fortifications covering the landward side of the naval base and of the city! More astounding, no measure worth speaking of had been taken by any of the commanders since the war began…I do not write this in any way to excuse myself. I ought to have known….The reason I had not asked about this matter…was that the possibility of Singapore having no landward defenses no more entered into my mind than that of a battleship being launched without a bottom.” (Churchill 48-49)

On January 24th, as British, Australian, Canadian, Indian, and Malayan forces retreated to the ‘bottomless battleship,’ blew the causeway, and prepared to defend it, the U.S. and Filipino forces moved to their final defensive positions on the Bataan peninsula.

On February 15th, with food, ammunition and water supplies nearly exhausted, the troops at Singapore surrendered. The Japanese took 70,000 Allied prisoners.

Meanwhile, in spite of poor rations, antiquated weaponry, and tropical disease, the U.S. and Filipino troops still held onto the Bataan peninsula. Their tenacity was admirable, but with no reinforcements coming the eventual outcome was clear.

On February 20th, the Philippine President evacuated. On March 11th, General MacArthur and his family left Corregidor Island, headed to Australia. Though the General promised “I shall return!” the fulfillment of that promise would be long coming.

General Wainwright was left in command, and the battles dragged on. In the beginning of April, the Japanese launched their last big offensive.

On April 8th, about 2,000 troops were evacuated to Corregidor Island. The exhausted remaining 78,000 defenders of Luzon surrendered.

The Japanese were not prepared to provide for so many POWs. The hungry, tired troops were forced to march about 60 miles north, where they were stuffed into boxcars and taken to imprisonment at Camp O’Donnell. On this, the infamous Bataan Death March, thousands of prisoners were beaten and killed. Thousands more died in Camp O’Donnell, in other POW camps, and in unmarked boats as they were shipped away for forced labor.

By May 6th, Wainwright’s forces on Corregidor couldn’t hold out any longer. They also surrendered, and were taken prisoner.

The beginnings of 1942 were dark for the Allies. However, soon names like “Midway” and “El Alamein” would hit the headlines. The conflict was far from over, but soon, the tide would begin to turn.

Many thanks for visiting!

Sources:

Maino, John. Frontlines WWII: Personal Accounts of Wisconsin Veterans. Appleton, WI. JPGraphics Inc, 2006. Print.

Buell, Hal (editor). World War II Album: The Complete Chronicle. New York. Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, 2002. Print.

Churchill, Winston S. The Hinge of Fate. Boston. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1950. Print.

Hyslop, Stephen G. and Neil Kagan. Eyewitness to World War II. Washington, D.C. National Geographic.

Time to catch up! It’s been forever since I’ve visited! My apologies!

This felt like you crammed a LOT into this one post. I’m kind of surprised you combined Bataan and Singapore into one post! There’s a lot of intense stuff here. I’ve heard a lot more about Bataan than Singapore, too — mostly about the death march. Man. I can’t imagine actually being there for that. Most of my Pacific Theater knowledge comes from stories from my grandfather or South Pacific, that bastion of historical accuracy.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Jon, glad you stopped by!

Uf, crammed is the word. This one took me a looooong time editing until I was satisfied with it. Maybe I should have tried to split it, but as they both fit in the same time frame and suffered the same fate, I thought it would work- still pretty happy with it, but I think next round I’ll be taking a smaller piece!

I’d heard of Bataan, but as always I’m finding out how much I don’t know. Picked up an excellent first hand account at the library last week- I’ll probably have to write about it. 🙂

The Pacific Theater really did get less attention- seems like it still does. (Though one of my favorite history blogs, G P Cox’s Pacific Paratrooper site, shares some really amazing, in-depth history from it. His dad served over there.) My grandpa was supposed to be sent to the PTO, trained in beach landings and everything. Then that whole “Battle of the Bulge” thing happened and they needed more fellas in Europe… but that’s another story.

LikeLiked by 2 people